IN TOUCH WITH THE MIMBRES, MOGOLLON, SALADO PROBLEM IN MULE CREEK NEW MEXICO, SOUTHWEST ARCHAEOLOGY FIELD SCHOOL PROBES FOR ANSWERS

Using Stone Axes DIANA TREVIZO and ALEXANDRA NORWOOD try to scrape the bark from the roof poles for the 13th Century Pueblo they are building near Mule Creek, New Mexico. They are building a adobe pueblo at the same time they are digging one up near Cliff.

JOE HALL screens fill from a new room block using window screen for every fourth load. Lots of info can fall through the cracks, like fish bones, turquoise bead.

Students in the 40-day Preservation Archaeology Field School sift through fill from a prehistoric Pueblo called the Dinwiddie Site in east central New Mexico. Fourteen students, the best of the best, 4.0 students were turned away, each student chosen brought a special something to the school. Unlike the traditional Field School this curriculum highlights preservation archaeology, an experimental component has the students building an adobe pueblo like the one they are digging up. Students also compete throwing 4′ Atlatl darts.

The peopling of the South West is a story best told by pottery. Ceramic pottery can tell archaeologist what they ate, where it was made, who made it and with whom the owner traded or aligned with…in a sense what was important to that culture and how successful or influential the culture was, how long it survived, and finally where did they go. But until tree ring dates, the chronology of all the ruins of the southwest, was a mystery until one afternoon when two pieces of charcoal crystalized everything that was known about the prehistory of the South West. In the one hundred years since man began probing the earth beneath their feet looking for secrets from the past much has been learned revealing to archaeologist how little they know or understand about early residents. So new strategies have evolved aided by the quick fresh minds of the next generation of archaeologist, new software that peels back the past, reveals pigment lost by time, using the sum knowledge from the past to build on future studies by incorporating all the data from all the earlier digs, aided by data from neighboring or regional sites. But more importantly, these new-age archaeologist, are tearing down fences that have long existed in the Cliff Valley and getting a first hand look at the prehistoric cultures that once called southwestern New Mexico home.

The 2015 Preservation Archaeology Field School staff is a combination of a lot of talent from Archaeology Southwest, Desert Archaeology, ASU and University of Arizona to structure a learning experience for a group of fourteen students who signed up for this opportunity to learn the general field and team work and the lab techniques necessary to extract science and knowledge from the soil.

Students are exposed to the principles of preservation archaeology, acquire the basic skills of excavation and survey, develop working strategies and write notes and reports that apply the logic of archaeological thinking to fieldwork, laboratory analysis, and applying the data we gather to answering anthropological questions. Finally think critically of issues about archaeological ethics.

As prehistoric man moved about he enjoyed a nomadic lifestyle of visiting old haunts places where they might have dropped some seed but most usually had luck hunting or gathering seasonal fruit. As more migrants entered the area, the nomadic Mogollon hunter found himself being crowded out and his old haunts now taken by the Anasazi fleeing their homes south east of Mesa Verde and looking for places to farm and live in safety. Local nomads soon were forced to stay at home and watch the crops.

The Mogollon and the Anasazi Material Cultures merge and disappear as the two groups diverge. Some Archaeologist believe the Kayenta Anasazi was traveling light, carrying what they could, leaving most of their culture behind. The nomadic Mogollon become seditary farmers, adopting some of the practices of their new neighbors, and soon they look pretty much alike. Except for ceramics! Archaeologist believe the Kayenta maintained contact with folks back home, perhaps opening trade connections with folks back home but meanwhile looping in the new immigrants settlements and establishing a trade network. When the bottom dropped out of the Colorado Plateau and everyone started looking for someplace wetter, the Kayenta knew where to go and who to stay with. They thought!

Rough corrugated ceramic pots are a clay signature for the Kayenta Anasazi and corrugated pottery left a trail from the Arizona Strip with some eventually reaching the Rio Grande and more was found south into Arizona Rim Country, visiting Mogollon Pueblos like Kinishba, Grasshopper Pueblo, Point-of-Pines, Cline Terrace. The Kayenta would build fortified hilltops above the floodplain along the Gila and San Pedro Rivers. Many of these sites are linked by signal towers to quickly communicate up and down the stream. The black and white pottery found at Salado sites suggests to some Archaeologist that the Kayenta continued to trade north to south until the end. But then Salado appears and everything changes. Four different archaeologist saw “Salado” arrive in different areas of the South West, but Harold Galdwin of Gila Pueblo received the credit for defining the Salado Culture but 85 years later we still disagree on much.

Agreement seems to be centering on Salado as a religion characterized by a distinct polychrome pottery and adobe compounds. The Salado message centered on fertility and cooperation, instead of honoring elite rulers, and some archaeologist have called it the first feminist movement, because in the day it was believed women did the most potting of clay and saved the South West from self destructing by intervening and preaching peace and working together. Others say shaman wheeled great power by producing the Mimbres Pottery characterized by “kill holes” which released the soul of the potter from the pot after his death.

The pottery design adapted reflected Mesoamerican imagery and changed in time but

researchers believe folks began thinking of themselves as Hohokam Salado or Kayenta Salado.

BREAKFAST can be the quiet time of the day as folks scurry around to make a lunch, finish breakfast and do the dishes and dash off for a full day in the sun.

The Archaeology Southwest Preservation Field School in it’s 5th season is an important component of our Upper Gila research, writes Karen Schollmeyer. “The results of this work contributes to Archaeology Southwest’s research on the formation and dissolution of late prehistoric communities. Dinwiddie’s occupation in the 1300s occurred during a period of substantial changes in the Southwest. Centuries earlier, large Classic Mimbres period villages were inhabited throughout the area. Around 1130, residents left these villages, and local populations remained small and scattered for the next 150-200 years. In the 1300s, large villages again began to form in the area. While people in the Upper Gila area were aggregated in large communities in the late 1300s, much of the rest of the southern Southwest was experiencing population decline. Our research examines the effects of the 14th century influx of residents to the Upper Gila. How did migrants from diverse cultural groups form cohesive villages? How did they structure social relationships with existing communities in their new home? How were social and natural resources affected by the long-term patterns of human population aggregation, dispersal, and re-aggregation? Our research at Dinwiddie will provide insights into these questions.”

Archaeologist Will Russell from ASU works with Alexander Ballesteros and Alisha Stalley to get the knack of working with a trowel in an archaeological dig. The Dinwiddie site was dug

Will Russell, one of ASU’s ceramics experts, oversees the trowel work and lectures the students crawling in the dirt “to move

from what you know to what you don’t”. Emphasizing the feel of the trowel and how it changes as it moves through the fill. “You can kinda feel these powdery, sugar forms on the floor, so you can see the visual clues…flecks of white (from the floor). You learn to read the vibrations he says. The trowel vibrates differently when hitting large particles and sounds differently–many different senses come in to play when excavating. Time is tight for the group they are half way through the 40 day class and they still have digging to do. Some of their time is filled with their preparation of displays for the community updates, reports, class trips to Silver City, the Gila Cliff Dwellings, Chaco Canyon, Acoma and the Zuni Pueblo. Screening is essential to separate the ceramics from the dirt and every fourth screen is window screen diameter to make sure nothing of importance is slipping through like the bones of fish and prairie dog which supplemented the prehistoric diet here in west central New Mexico.

My first morning in Mule Creek where the field school is headquartered at the Rocker Diamond X Ranch there was a morning drizzle and students scurried around before sunrise eating breakfast, brushing teeth and making lunches and preparing for their day. Everyone has a job each day, each serves as a cog in the wheel and things happened smoothly until dinner when Mary shows up with dinner for the hungry staff, students and visitors. Students divide up into the field crews, survey and the experiemental crew who spend the day with archaeologist Allan Denoyer who is a master flintnapper and he and his crews are putting the finishing touches on a Salado Pueblo which they have constructed during the past field seasons. Denoyer has reverse engineered the adobe pueblos the field crews are excavating at the Dinwiddie Site with hopes the students will gain a greater insight into pueblos by building one as well as digging up what remains of numerous melted room blocks. Students learn to skin the timbers using stone axes and how to construct the roof. All knife work is from obsidian blades that slice as quick and accurately as steel.

Field Supervisor LESLIE ARAGON pours off buckets of fill taken from the Dinwiddie Ruin dig. Three days will be spent back-filling the excavations with the soil they pain removed.

Students are responsible for blog posts, and displays for community outreach projects which hold public meetings in the region giving archaeologist the opportunity to explain to residents what they are looking for, what they found and often those exchanges open doors to archaeology not presently known and the field school survey crew go out looking for sites people tell them about. One student turned up a ten-room pueblo which was previously unrecorded. The survey crew often camps, to allow more boots on the ground than drive time. The easy duty appears to be the field work until you see there is no shade, students on their hands and knees with metal trowels pushing back the dirt from a solid polished adobe floor.

For the past few days they have turned up almost 50 ceramic marbles of varying diameters and for whose purpose is unknown, today, they turned up a nice 3/4 groove axe head next to the unique t-shaped doorway recently unearthed. At room one, a cry alerts us, a metate and a mano, together, intact–beautifully preserved.

A vocational archaeologist working in the 1960s and 1970s and some early work contributed important information to our knowledge of Salado archaeology.  These excavations did not follow collection and reporting standards of their era, and information from these older excavations is now unavailable. Collections from these excavations were housed in private museums and everything disappeared upon their owners’ deaths, scattering collections so that they are no longer available for research. The Dinwiddie site saw several field seasons of avocational excavation, with 37 rooms in two room blocks partially excavated by Jack and Vera Mills (1972) they are thought to have taken more than a hundred pots from these rooms, some of those pots reside today in Safford, Arizona at the Museum for Eastern Arizona State.

These excavations did not follow collection and reporting standards of their era, and information from these older excavations is now unavailable. Collections from these excavations were housed in private museums and everything disappeared upon their owners’ deaths, scattering collections so that they are no longer available for research. The Dinwiddie site saw several field seasons of avocational excavation, with 37 rooms in two room blocks partially excavated by Jack and Vera Mills (1972) they are thought to have taken more than a hundred pots from these rooms, some of those pots reside today in Safford, Arizona at the Museum for Eastern Arizona State.

Archaeology SouthWest’s interest in the Cliff Valley “Dinwiddie” site came as a part of the Upper Gila research, using the field school as an important component of the research, searching for the formation and dissolution of late prehistoric communities. Dinwiddie’s occupation in the 1300s came at a time of big changes in the Southwest. Centuries earlier, large Classic Mimbres period villages had inhabited throughout the area. Around 1130, those residents left these villages, and local populations remained small and scattered for the next 150-200 years. In the 1300s, large villages again began to form. People in the Upper Gila moved into large communities in the late 1300s, while much of the southern Southwest was experiencing population decline. Karen Gust Schollmeyer, believes the Dinwiddie dig will provide insights into the 14th century influx of residents to the Upper Gila. In 2008, Archaeology Southwest received a National Science Foundation grant to study the Salado phenomenon in the greater Upper Gila region of southwestern New Mexico, an area traditionally assigned to the Mogollon archaeological culture area

Marcy Pablo, a Tohono O’odham from Topawa prepares basket weaves for their “Community OutReach” Pablo intends to assist New Mexican residents to begin weaving their own basket using her starts. The School tries to lower barriers between locals and archaeologist by sharing their research with locals.

JOE HALL (Sierra Vista) and DEVINNE FACKELMAN (Allendale, Mich.) together dug up this Metate and Mano while searching for a wall.

“The Archaeology Southwest Field School was a life changing experience. I learned more about the southwest in those 6 weeks than in my two and a half years prior exploring in Southeastern Arizona. I had just graduated from Cochise College with a degree in Anthropology and immediately attended the ASW Field School with no real experience in archaeology. I am so fortunate to be given such a great opportunity to learn. From the field trips to the guest lectures, there was never a dull moment around the camp. Even in our down time we used the skills we had learned from experimental archaeology and our guests to do assorted crafts. The research the group of students accomplished was also inspiring, and attention grabbing. Post-field school I am more interested in Archaeology than ever. I plan to use my Non-Profit Leadership and Management degree at Arizona State University to get myself and others involved in the Archaeology field.”..Joe Hall

This Pueblo erected with the energy of field school students but with the same technology that the Mogollon used.

Field school students had some unstructured time in the evenings. But most worked on their field reports, blogs and burning designs

Archaeozoology – The study of animal remains, usually bones, from the past. Alexandra Norwood (Pasadena, CA) enjoys the final product.

Field Supervisor Will Russell (ASU) fields questions from Bill Jamison, a Duck Creek resident for the past forty years. Jamison mentioned about 10 years ago, a burial fell into the creek.

The next morning at the Dinwiddie Dig a 40 year resident of the Duck Creek Community dropped by to visit the site and Will Russell was able to share with Bill Jamison the Field School’s focus and share with him some of what had been found. Jamison pointed out for a decade a burial eroded out of the river bank

and eventually was washed away. He did say a friend now living in San Diego had collected enough sherds to completely restore three pots and Russell asked him if photos were available or if they could be sent Another lead to another piece of the puzzle.

VICTORIA BOWLER shows ALEXANDAR BALLESTEROS how to throw ATLATL darts. Bowler works as an archaeologist and interpreter at Fort Bowie and Chiricahua National Monument and feels this field school will allow her to put these new ideas into practice.

Flintknapper Allan Denoyear made these two points at the field school for his orientation discussion.

Digital Antiquity is a nonprofit grassroots effort to get all Archaeological data archived by creating a multi-institutional, non-profit organization dedicated to overseeing the use, development, and maintenance of the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR), an international repository for the digital records of archaeological investigations, organizations, projects, and research.

Students listen to a digital workshop produced by ASU’s Jodi Reeves-Flores on Digital Antiquity’s tDAR, an archaeological online data base where data input will be preserved, and reinterpreted as a piece of the whole.

One of Digital Antiquity’s key objectives is to foster the use of tDAR and ensure its financial, technical, and professional sustainability. Use of tDAR has the potential to transform archaeological research by providing direct access to digital data from current and historic investigations along with powerful tools to analyze and reuse it.

Digital Antiquity was created through the collaboration of archaeologists, library scientists, and administrators from the Archaeology Data Service, the University of Arkansas, Arizona State University, the Pennsylvania State University, the SRI Foundation, and Washington State University.

By enhancing preservation of and access to digital archaeological records, the mission of Digital Antiquity to permit researchers to more effectively create and communicate knowledge of the long-term human past; enhance the management, interpretation, and preservation of archaeological resources; and provide for the long-term preservation of irreplaceable records

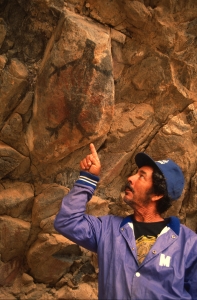

Using Decorrelation Stretch to Enhance Rock Art Images

By Jon Harman, Ph.D. (dstretch@prodigy.net) Web site: http://www.DStretch.com

Decorrelation stretch, an image enhancement technique first used in remote sensing, can be usefully applied to rock art. In pictograph images from Baja California, Utah and Arizona I demonstrate its ability to bring out elements nearly invisible to the eye and to improve visualization of difficult sites. A decorrelation stretch plugin to the imaging program ImageJ is available from the author, free for personal use. It’s free but suggested contribution is $50. You can make a contribution via PayPal. My account is JonHarman “at” prodigy.net, if you want to send a check you will find his address on the email he sends back.

Lizard shaped pictograph in a cave near Mulege BAJA Sur…. This rock art is made with paints perhaps from crushed rock with iron.

Decorrelation stretch was developed at JPL and it has been used in remote sensing to enhance multispectral images. NASA used it to enhance Mars Rover images. DStretch has become a very useful tool for archaeologists

Filtered photograph of Lizard now only shows a hand print which was made by an artist filling his mouth with paint and blowing it through a reed toward his hand on the rock.

involved in the study and documentation of rock art. Its enhancement techniques can bring out very faint pictographs almost invisible to the eye. Subtle differences in hue are enhanced to puzzle out faint elements. Use of DStretch is simple as just hitting a button, but it also contains sophisticated tools for the manipulation of false color images. Because the enhancement works by increasing differences in hue, the technique gives better results for pictographs than petroglyphs.

The technique applies a Karhunen-Loeve transform to the colors of the image. This diagonalizes the covariance (or optionally the correlation) matrix of the colors. Next the contrast for each color is stretched to equalize the color variances. At this point the colors are uncorrelated and fill the colorspace. Finally the inverse transform is used to map the colors back to an approximation of the original. DStretch supports several different colorspaces, the image is converted from RGB to the colorspace, the calculation and transformation is performed, and then the colors are converted back to RGB before writing into a digital image.

The most common color found in pictographs is red, followed by black, then white, then rarely other hues. Often the rock shelter or cave wall is reddish or blackened. There are common types in the color distributions of pictograph images and this causes a consistency in the decorrelation stretch enhancements. DStretch works well to enhance red pigment but suppresses white and blacks. By bringing out the red painting and suppressing the background shades it can help clarify image composition.

DStretch is a plugin to ImageJ which is a full-featured imaging program. It is written in Java and can run on PC’s, Mac’s and Linux computers. When the button is pressed the plugin calculates the covariance matrix of the image colors (within the chosen colorspace) and then determines the transformation. Different decorrelation results are possible by selecting different parts of the image.

Different colorspaces give different results. DStretch has implemented the algorithm in the standard RGB and LAB colorspaces and also in the colorspaces: YDS, YBR, YBK, LDS, LRE. These colorspaces are modifications of the YUV or LAB colorspaces that give good decorrelation stretch results on images of rock art. The YDS and LDS colorspaces are good for general enhancements and can bring out faint yellow pigments. YBR and espeically LRE enhance reds. YBK can help with black and blue pigments and also enhances yellows well. The user can design their own colorspaces using the YXX and LXX buttons. The enhanced image is false color, the color scan be radically different from the original. In Expert Mode DStretc has the ability to shift the hues in the enhanced image to increase contrast.

CLICK HERE FOR SLIDE SHOW OF ROCK ART USING FALSE COLOR TO PRODUCE ADDITIONAL DETAIL…

http://pkweis.photoshelter.com/gallery/ROCK-ART-FILTERS/G0000oUHzJSUXcUI

Each image enhances differently, depending on its own unique distribution of colors. Another useful enhancement technique, not related to decorrelation stretch, is the manipulation of the hue and saturation of the image. DStretch (in expert mode) can do hue histogram equalization and saturation stretching. DStretch also contains a tool that allows a region of the enhanced image to be isolated by hue and then added back to the original image. This can be used to isolate an enhanced element then return it to the original image.

http://pkweis.photoshelter.com/gallery/ROCK-ART-FILTERS/G0000oUHzJSUXcUI

3D Scanning: Cultural Heritage and the Arts

Using 3D or “White Light” Scanners can uncover details from the past and today there is no better way to record a complex object than with a high resolution 3D white light scanner. The fringe projection method used in 3D white light scanning make non-contact digitization of art and sculpture and historical artifacts possible. Direct comparisons can be made of dimension and shape. Structured light Scanning allows revisitation of any object over time, creation of databases, redrawings of cross sections and 3D volume calculations. Today 3D scan data has a growing value in archaeology, paleontology and cultural heritage, collection of 3D scan data provides a digital archival record allowing access in remote locations, and the ability to produce replicas useful for exhibits.

One strategy under consideration at the Preservation Field School is the possibility of being able to actually see the “fingerprints” of the potter in ceramics. If that study moves forward there is a hope that not only will archaeologists know where the “Ancient Ones” went, they may be able to follow the fingerprints of a single women walking across an prehistoric landscape to her final resting place.

Kristin Safi in this month’s Kiva Journal outlines his “least cost” migration routes from the San Juan region to the Rio Grande Pueblo area. In this study 1200 possible routes are identified but many overlap and others had more costly terrain boiling the study down to 30 routes but when known archaeological sites were factored in, five routes were identified as the probable exodus path taken by the Kayenta Anasazi as they left the Northeast Arizona. Three of the routes probably were used by the later migrations because closer Pueblos were filled up earlier by early migrations. As for the question, “Where did the Ancient Ones go!” Not only do we know where the Kayenta went, we know why. FEAR!

<a href=” SPANISH TRANSLATIONS:">

BIRDING IN THE SOUTHWEST, TAKE YOUR SCOPE ! NO MATTER WHERE YOU ARE IN ARIZONA THERE IS A HOT BIRDING PARADISE AT A WETLAND NEAR YOU !

SouthEast Arizona comes out number TWO on a list of twenty-five of the best birding locations in the Southwest. For one thing Southeast Arizona is the hummingbird capitol of the United States, particularly in August. Ramsey Canyon in the Huachuca Mountains is the place to head toward for hummingbirds in July or Augustlike the Blue-throated, Broad-billed, Black-chinned. The Arizona-Sonoran Desert Museum is said to attract desert species including Verdin, Gilded Flickers and Gila Woodpeckers. Cave Creek which runs through Portal in the Chiricahua Mountains along the South Fork Trail may yield Elegant Trogan or Flame-colored Tanager and owls. Madera Canyon/Florida Wash/Santa Rita Mountains area is known for its Magnificent Hummingbirds, Buff-collared Nightjar, Cassin’s or Botteri’s Sparrows at Florida Wash. The Strickland’s Woodpecker is found at higher elevation and the Elf Owls nests in the area. The Patagonia/Sonoita Creek is famous for its roadside rest area, watch for the Gray Hawk, Thick-Billed Kingbird, and Rose-throated Becard. Sonoita Creek Sanctuary is a hot birding spot, but may not be open every day .

NEED TO NAME A BIRD YOU HAVE SEEN TRY CLICKING HERE ….

BE SURE TO CHECK OUT THIS INCREDIBLE BIRDING BLOG CALLED: TOMMY’S BIRDING EXPEDITIONS

GREAT NEWS ! PATAGONIA’S PATRON’S BIRD HAVEN TO BE PRESERVED

To reach Paton’s Birder Haven from Tucson, take Interstate 10 east to Arizona 83 and follow 83 south to Sonoita. From Sonoita, take Arizona 82 southwest to Patagonia. In Patagonia, take Fourth Avenue west from Arizona 82 four blocks to Pennsylvania Avenue. Turn left, south, on Pennsylvania. The haven is the first house on the left after the avenue crosses a small creek.

Tucson and Southern Arizona is one of the best bird-watching destinations in the United States. More than 500 bird species have been observed here at different altitudes throughout the year. Hummingbirds are especially plentiful; more than 150 species have been seen in a single day during the spectacular spring and fall migrations.  Public gardens and state and national parks surrounding the city are havens for various winged natives and seasonal visitors. A short drive south of Tucson, in Southern Arizona’s rolling grasslands and lofty mountain ranges, one can find the Elegant Trogan, Broad-billed Hummingbird, Vermilion Flycatcher and many other species. Bird-watching festivals and nature walks are very popular during migration times.

Public gardens and state and national parks surrounding the city are havens for various winged natives and seasonal visitors. A short drive south of Tucson, in Southern Arizona’s rolling grasslands and lofty mountain ranges, one can find the Elegant Trogan, Broad-billed Hummingbird, Vermilion Flycatcher and many other species. Bird-watching festivals and nature walks are very popular during migration times.

Bird watching may be a quiet market, but Paul Green from the Tucson Audubon Society said cash is flying in with the help from visitors.

“When they come here they spend money mainly on food, lodging transportation and that’s worth to the state about 1.5 billion dollars a year. And Pima County more than 300 million dollars a year,” Green told KVOA TV. An avid bird watcher for more than 60 years, Richard Carlson said tourists come to Tucson with binoculars in hand to watch more than 400 species, while bringing in some big bird bucks.”If it’s a really great bird people will be buying airline tickets that day to come to that spot,” said Carlson. Business owners in Madera Canyon said if it wasn’t for the birding community, they would notice a substantial loss of business. “We probably have 50 percent of our clientele are bird watchers. Out of state people are flying into Tucson, renting a car and obtaining lodging here with us,” said Luis Calzo. “We’re looking to work more with businesses there in town to market the benefits of coming to Tucson for birding,” says Green.

10 best birding spots in southern Arizona

1. Chiracahua National Monument

2. Portal

3. Ramsey Canyon Preserve

4. Whitewater Draw

5. Muleshoe Ranch

6. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area

7. Buenas Aires National Wildlife Refuge

8. Sabino Canyon

9. Madera Canyon

10. Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve

The first thing you notice about the Sweetwater Wetlands is that it doesn’t smell so sweet. But the restored wetlands has brought back wildlife and habitat once lost to the Santa Cruz River Valley and now through recycling sewage, it gives new life to this river. The wildlife is thriving here, as attested by two visiting photographers who frequently come by like Tucson lawyer Steve Kessel and R.C. Clark, both drop by all the time and see what is happening. Kessel said he has visited for an hour or two most days for the past year. He recently got “skunked” or saw nothing for five days, and on day five he stumbles across a momma bobcat watching her two kittens play and scamper about. Being bobcats they could care less if anyone watched or made pictures. After recovering from the awesome bobcat encounter, Kessel comes across the memorible sight of “four Giant Egrets, they have black legs, orange bills and are powder white, you will never forget that sighting,” says Kessel fueled by those encounters he is now back out walking the pathways with Clark enjoying the deepening shadows, richer light and constant bird chatter. “All the birds you want to see, all types are right here! The raptors, the songbirds, owls and ducks all find there way here and you never know what you are going to see.”

STEVE KESSEL (RIGHT) AND R.C. CLARK (LEFT)

Sweetwater Wetland is a constructed wetland located in Tucson between I-10 and the Santa Cruz River, near Prince Road. Built in 1996, it helps treat secondary effluent and backwash from the reclaimed water treatment system at adjacent Roger Road Wastewater Treatment Plant. Sweetwater serves as an environmental education facility and habitat for a wide variety of wildlife. Sweetwater Rarities seen here over the years include Least Grebe, Chestnut-sided Warbler, and many others. A group of Harris’s Hawks is often reported in the large eucalyptus trees north of Sweetwater, near the Roger Road Wastewater Treatment Plant. Sweetwater Wetland consists of several ponds surrounded by cattails, willows, and cottonwoods. Ducks visit the ponds while Red-winged, Yellow-headed, and Brewer’s blackbirds frequent the cattails. Thick stands of saltbush provide cover to Song Sparrows, Abert’s Towhees, wrens, and many other species. Paths, both paved and unpaved, visit all the ponds and give a view to the large detention basins to the south which attract wading birds and shore birds.

The hours for Sweetwater is 6am-6pm, opening 8am on Mondays. Tuesday to Sunday it opens at Dawn to approximately one hour after dusk Monday: 8 AM to one hour after dusk. Gates are locked 1 hour after dusk, don’t get locked in! The Wetland is closed on Monday mornings usually from late March to mid-November.

FREE BIRDING TRIPS IN TUCSON …..CLICK HERE

Trips hit all the important spots plus some out of the way locations but try Tucson’s Sweetwater Wetlands on Wednesdays. Join the TUCSON AUTUBON for an easy walk through the Sweetwater wetlands to see waterfowl in the hundreds, regular and visiting warblers, and several exciting species hiding in the reeds. Birders of all experience levels welcome! Contact leader for start time and to sign up, mike.sadat@gmail.com

See the Sweetwater online bird checklist.

LISTING OF BIRDING FESTIVALS ALL ACROSS THE UNITED STATES

Every year a part of Apache Junction, Arizona is transformed into a 16th Century European Country Fair when the Arizona Renaissance Festival opens to the public during the months of February and March.  One of the favorite shows is the Birds of Prey show on the grassy green next to the bird castle called "The Falconer's Heath." You get to see up close the awesome power of nature's most exciting birds. The time we were there they had a falcon tear through the air like a little winged thunderbolt. Then there was a scary South American vulture that cleaned a whole turkey leg in a few seconds. Like a piranha with wings.

One of the favorite shows is the Birds of Prey show on the grassy green next to the bird castle called "The Falconer's Heath." You get to see up close the awesome power of nature's most exciting birds. The time we were there they had a falcon tear through the air like a little winged thunderbolt. Then there was a scary South American vulture that cleaned a whole turkey leg in a few seconds. Like a piranha with wings.

The Arizona Renaissance Festival is a wonderful combination of amusement park, shows, comedy, music, feats of daring, street performers, shopping, and indulging. The Festival is spread out over 30 acres, and it is easy to spend an entire day there. Arizona Renaissance Festival will be open every Saturday and Sunday from February through March. Hours are 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. It is open rain or shine. Take State Highway 60 East, east of Apache Junction, just east of Gold Canyon Golf Resort, is the Renaissance Festival?

Bearizona Wildlife Park is proud to be the new home for the High Country Raptors, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting raptor conservation through education. The High Country Raptors are stationed in Fort Bearizona. There are three scheduled free-flight shows daily, 11am-1-3:00pm, during these shows, visitors come face to face with hawks, owls, falcons and other raptors. Programs have included “on the fist” demonstrations and dramatic “free flight” shows, all with a narrative on natural history, conservation and interesting facts while entertaining audiences of all ages.

At the conclusion of every show the handlers will have the birds throughout Fort Bearizona “on the fist” for visitors to get an up-close look and answer any lingering questions they might have.

Directions to help you get there. Parking is free

Bearizona Wildlife Park

1500 Historic Route 66, Williams, AZ 86046

(928) 635-2289

Hours: Wednesday 8:00 am – 4:30 pm

The barn owl is recognizable by its ghostly pale color and heart-shaped facial disc. The barn owl is one of the most wide-ranging birds in the world. Barn owls do not hoot, instead emitting a long, eerie screech. They also hiss, snore and yap. With its asymmetrical ears, the barn owl has the most acute hearing of any animal.

When we first opened the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum‘s hummingbird aviary, writes Karen Krebbs, we had no idea whether or not any of the seven species of the birds on exhibit would breed and rear young.  Since opening day, however, we’ve seen Costas, Broad-billed, Black-chinned, Anna’s, and Calliope hummingbirds nest, lay eggs, and rear young. There have been a total of 114 nests built, 186 eggs laid, 116 birds hatched, and 102 birds fledged. No other zoological institution can boast of such success!

Since opening day, however, we’ve seen Costas, Broad-billed, Black-chinned, Anna’s, and Calliope hummingbirds nest, lay eggs, and rear young. There have been a total of 114 nests built, 186 eggs laid, 116 birds hatched, and 102 birds fledged. No other zoological institution can boast of such success!

For more information, visit High Country Raptors.

Arizona Sonora Desert Museum

2021 N Kinney Rd

Tucson, AZ 85743

(520) 883-2702

desertmuseum.org

Arizona’s unique combination of geography and climate supports more than 500 species of birds. That’s almost half the total of all bird species that can be found in the United States and Canada!

Feeding along side of one of America’s grandest mirgratory flyways, the Rio Grande River which winds through New Mexico provides feed and rest for migrating birds, like these Sandhill Cranes.

Welcome to registration for the 21st Annual Wings Over Willcox Birding & Nature Festival

If you have any questions call 1-800-200-2272 To register online click here…

15 Jan 2014 – 19 Jan 2014 includes Sandhill Cranes Tours – Thousands up close and personal, southwest mountain birds, wildlife photography, and beginning birdwatching. Tours are limited and many fill early. Contact Terry Rowden with the Willcox Chamber of Commerce and Agriculture in Willcox Call the Chamber of Commerce at 520-384-2272, 800-200-2272 or go online at Website: http://www.wingsoverwillcox.com

1/17/2014 Friday

Daylong Photography Remaining Tickets: 7 Meet at WCC: 5:50 AM Return: 4:00 PM $100.00

Spend time with two wildlife photography experts THOMAS WHETTEN AND GEORGE ANDREJKO at Whitewater Draw and other southeastern Arizona sites, photographing Sandhill Cranes and other birds. Less than ½ mile of easy walking. Intermediate to Advanced Photographers. Includes lunch, drinks. A visit to the Willcox Playa Wildlife Area offers a rich experience in an otherwise desert environment. Bird-watching at the playa and associated habitats is a fantastic way to spend a day or a weekend. Birds that can be seen range from shorebirds to the always enjoyable flocks of sandhill cranes that are the focus of the annual Wings over Willcox birding festival where each winter, Bird-watching and photography takes center stage as hundreds of species of birds visit the Willcox Playa Wildlife Area. Growing interest in viewing wildlife sparked this annual event, Wings over Willcox.

Tucson Audubon’s Harvest Festival …August 13–17, 2014

Bring the family to Tucson Audubon’s Mason Center to celebrate the edible bounties of the Sonoran Desert. There will be vendors and exhibitors, family activities, guided bird walks, sustainability tours, food trucks, a plant sale, and opportunities to mill your mesquite pods into delicious, gluten-free flour. Tucson, AZ, US Tucson Audubon Contact: Kara Phone Number: 520-629-0510 Website: http://www.tucsonaudubon.org/harvestfestival

THE TUCSON’S VALLEY AUDUBON CHRISTMAS COUNT WILL BE HELD DECEMBER 15, 2014

The National Audubon Society has conducted Christmas bird counts since 1900. Volunteers from across North America and beyond take to the field during one calendar day between December 14 and January 5 to record every bird species and individual bird encountered within a designated 15-mile diameter circle.

WINGS OVER WILLCOX

15 Jan 2014 – 19 Jan 2014

25,000+wintering Sandhill Cranes; area hosts many hawks,eagles,&falcons; also20+sparrow species. Bird tours(expert guides),free seminars, & nature expo(vendors & live animals). Banquet speaker Bill Thompson III (“BirdWatcher’sDigest” & “BilloftheBirds” blog) on “Perils and Pitfalls of Birding”. For non-birders–tours & free seminars on local history, geology, natural history, agriculture &astronomy. Sierra Vista, AZ, US

Tours include Sandhill Cranes – thousands up close and personal, southwest mountain birds, wildlife photography, and beginning birdwatching.

Tours are limited and many fill early. Contact the Willcox Chamber of Commerce at 520-384-2272, 800-200-2272 or go online at http://www.wingsoverwillcox.com

ARIZONA is home to more than 500 species of bird which bring $1.5 billion of tourism to the area.

In Parker, Arizona since the 1930’s the large cottonwood-willow forests along the lower Colorado River have largely disappeared. The Bill Williams River National Wildlife Refuge contains the last extensive native riparian habitat in the Lower Colorado River Valley. For many species of birds this is the only habitat remaining in the area for breeding; for others, it is a vital stopover during migration. The refuge is also home for the largest populations of many resident birds found in the valley. Habitats found on the refuge include desert uplands, marshes, riparian forests, and the open water of the delta. The diversity and uniqueness of the Bill Williams River NWR provides visitors with a rewarding birding experience.

Neotropical migrant landbirds are those species of land birds that nest in the United States or Canada, and spend the winter primarily south of our border in Mexico, Central or South America, or in the Caribbean. Many of them, including conspicuous or colorful hawks, hummingbirds, warblers, and tanagers, and less colorful but no less important flycatchers, thrushes, and vireos, are experiencing population declines due to widespread loss of habitats important for their survival. Preservation of many different habitats for nesting, wintering, and migratory stopover sites is becoming vital for the survival of many of these birds.

The Whooping Crane (Grus americana), the tallest North American bird, is an endangered crane species named for its whooping sound. In 2003, there were about 153 pairs of whooping cranes. Along with the Sandhill Crane, it is one of only two crane species found in North America. The Whooping Crane’s lifespan is estimated to be 22 to 24 years in the wild. After being pushed to the brink of extinction by unregulated hunting and loss of habitat to just 21 wild and two captive Whooping Cranes by 1941, conservation efforts have led to a limited recovery. As of 2011, there are an estimated 437 birds in the wild and more than 165 in captivity.

Havasu National Wildlife Refuge encompasess 37,515 acres adjacent to the Colorado River. Topock Marsh, Topock Gorge, and the Havasu Wilderness constitute the three major portions of the refuge. Habitat varies from cattail-bulrush back waters and shrubby riparian lowlands to steep cactus-strewn cliffs and mountains. Due to the southery location of the refuge it is primarly a wintering area and stopover point for migrating birds.

The area in and around Lake Havasu City is rich in bird watching opportunities, with more than 350 species identified in the local area. Consult the Mohave County Field Check List to learn of the possibilities. One of the best ways to observe waterfowl is from a kayak or canoe in early morning. Free non-motorized boat launches are located at Castle Rock Bay Canoe Takeout Point and Mesquite Bay, maintained by U.S. Fish & Wildlife.You’ll find cattails and sandbars for loons, grebes, ducks, larids, raptors and coots. Horned Grebes favor this area in winter, along with the more usual grebes and flotillas of coots. For land based excursions, try the free fishing piers at Mesquite Bay on London Bridge Rd., just north of Industrial Blvd., which are open 24 hours. The walking trail and Arroyo-Camino Interpretative Garden at Lake Havasu State Park offers opportunities for both land and water bird viewing.

One of the best ways to observe waterfowl is from a kayak or canoe in early morning. Free non-motorized boat launches are located at Castle Rock Bay Canoe Takeout Point and Mesquite Bay, maintained by U.S. Fish & Wildlife.You’ll find cattails and sandbars for loons, grebes, ducks, larids, raptors and coots. Horned Grebes favor this area in winter, along with the more usual grebes and flotillas of coots. For land based excursions, try the free fishing piers at Mesquite Bay on London Bridge Rd., just north of Industrial Blvd., which are open 24 hours. The walking trail and Arroyo-Camino Interpretative Garden at Lake Havasu State Park offers opportunities for both land and water bird viewing.

Leaving early the first morning, take Highway 95 South for approximately 20 miles to the Bill Williams River National Wildlife Refuge. The refuge office is located between mileposts 160 and 161. There is plenty of parking. The Visitor Center is open from 6:30 AM to 4:00 PM, Monday through Friday and from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM on weekends. Stay as long as you like, then return to Lake Havasu City for dinner.

Leaving early the next morning, take Highway 95 north to I-40 West (direction of Needles/Las Vegas) to the Havasu National Wildlife Refuge. Exit I-40 at exit marker 1. It is posted as Havasu National Wildlife Refuge; follow the signs to the refuge. There is plenty of parking. The Visitor Center is open from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM, Monday-Friday.

Imperial National Wildlife Refuge consists of approximately 25,000 acres along the lower Colorado River. Spring and Fall offer the greatest variety of birds and the best birding opportunities. Also, the refuge is important as a wintering area for Canada geese and many species of ducks. Maps and regulations are available at the refuge headquarters for your convenience.

Little Picacho is a hot spot in the summer and this bird and his buddies look for the unprepared.

Welcome to the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM’s) Yuma District. The District encompasses over 2.5 million acres of land, of which almost 1.25 million acres are public lands. These are your lands to enjoy and protect. They are managed and administered by the BLM to maintain the multiple use values of all resources, for you, and for future generations.

The Yuma District encompasses over 2.5 million acres of land, of which almost 1.25 million acres are public land along the entire 280-mile length of the lower Colorado River, from Davis Dam along the Nevada border on the north, to the border with Mexico on the south. It includes portions of Arizona and California and contains a wide diversity of wildlife habitat.

Winter visitors flock to the Yuma Colorado River each fall for the warmer temps and bird-watching.

Cibola National Wildlife Refuge on the Colorado about 40 miles north of Yuma includes 18,300 acres of riparian habitat with more than 288 species of birds, including endangered southwestern willow flycatcher and Yuma clapper rail; desert tortoise, mule deer, bobcats and coyotes. Use the visitor center, and enjoy the 3-mile auto tour loop and 1-mile nature trail but camping is not permitted.

This list of 271 species highlights birds found along The San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area includes over 56,000 acres in Cochise County, Arizona. Extending approximately 40 miles northward from the Mexican border to a few miles south of St. David, the NCA represents the most extensive, healthy ripari an ecosystem remaining the desert Southwest. The Bureau of Land Management manages the area to protect and enhance the existing riparian habitat and wildlife communities, as well as provide for recreational use, cultural interpretation, and educational opportunities.

an ecosystem remaining the desert Southwest. The Bureau of Land Management manages the area to protect and enhance the existing riparian habitat and wildlife communities, as well as provide for recreational use, cultural interpretation, and educational opportunities.

The 40,000-acre Cienega de Santa Clara is a principal stopover point for migratory waterfowl and home to hundreds of bird species, including the endangered Yuma clapper rail, a secretive shorebird whose cry sounds like hands clapping.

Santa Clara Wetlands lies in Mexico in the Colorado River Delta and serves as a flyby rest stop.

The 40,000-acre Cienega de Santa Clara is the largest remaining wetland in the Rio Colorado delta; it supports endangered bird and fish species. The wetland is maintained by agricultural drainage water discharge from the USA which may be diverted to the Yuma Desalting Plant in the future. The distribution of marsh plants is related to salinity and water depth within the Cienega. During 8 months of unplanned flow interruption due to the need for canal repairs, 60-70% of the marsh foliage died back. Green vegetation was confined to a low-lying geologic fault which retained water; though the vegetation proved resilient, prolonged flow reduction would unavoidably reduce the size of the wetland and its capacity to support life.

“I’ve been birding the Verde Valley and Flagstaff area for 13 years now and know it to be a wonderful spot where anyone can turn up a real gem at any time,” says Tom Linda, a birder and popular guide at the Verde Valley Birding & Nature Festival. The annual Nature Festival takes place at Dead Horse Ranch Park in Cottonwood, Arizona, during the last weekend in April.

The Continental Lake on Flagstaffs northeast side at sunrise.

SOUTHWEST BIRDING HOTSPOTS OR RARE BIRD ALERTS

SOUTHWESTPHOTOBANK.COM PHOTOS GALLERY FOR SOUTHWEST WILDLIFE…CLICK HERE

Condor Viewing in the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument

ARIZONA STRIP’S VERMILLION CLIFFS IS HOME TO THE CONDOR

California condors were placed on the federal Endangered Species list in 1967. Only 22 condors were known to remain in 1982, while today the world population exceeds 400, with over 225 condors living in the wild. Approximately 75 condors reside in the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument. In Arizona, reintroduction is being conducted under a special provision of the Endangered Species Act that allows for the designation of a nonessential experimental population, under this protections for a species are relaxed, allowing greater flexibility for management of a reintroduction program.

Since December of 1996, program personnel have released condors every year. Each condor is fitted with radio transmitters and is monitored daily by field biologists. Directions to visit the condor viewing site in Arizona, drive north on Highway 89 out of Flagstaff, Arizona. Turn left onto Highway 89A toward Jacob Lake and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Drive approximately 40 miles (past Marble Canyon, Vermilion Cliffs, and Cliff Dwellers lodges); turn right onto House Rock Valley Road (BLM Road 1065) just past the House Rock Valley Chain-Up Area. Travel approximately 2 miles to the condor viewing site on the right. Atop the cliffs to your east is the location where condors are released, and a good place to see condors year round. In winter months, condors frequent the Colorado River corridor near Marble Canyon, which is east of the condor viewing site on Highway 89A. In the summer months condors are seen frequently at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon and at Kolob Canyon in Zion National Park north of St. George, Utah on Interstate Route 15. Hours: 7:45 a.m.-5:00 p.m. Monday through Friday 10:00 a.m.-3:00 p.m. Saturday. Closed Sunday.

Vermilion Cliffs National Monument 345 E. Riverside Drive St. George, UT 84790-6714 (435) 688-3200

photographed in Southern Arizona at Parker Canyon Lake.

Spring in the Chiricahua Mountains — BIRDING LINKS

Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory

P.O. Box 5521

Bisbee, AZ 85603-5521

(520) 432-1388

The Sulphur Springs Valley is a winter paradise for birds of prey. Up to twenty species may be found here between November and March, including eagles, falcons, buteos, accipiters, harriers, kites and owls. The Southern Arizona Bird Observatory Hawk Stalk tours take you down highways and back roads in search of these magnificent predators and other species that share their habitats. Along the way, your expert naturalist guides will share their knowledge of the identification, behavior, ecology, and history of the valley’s raptors, Sandhill Cranes, sparrows, and other wintering and resident birds. These all-day tours depart at 8 a.m. from downtown Bisbee and return around 4 p.m. Participants travel in a 15-passenger van (or minivan for groups of 5 or fewer), with frequent stops for roadside birding and short walks. The group will stop for lunch. Tours begin Thanksgiving weekend and continue most weekends through February. Please register at least one week in advance. $75 per adult for members of SABO, $85 for non-members; $40/members, $45/non-members for children age 10-16 when with by an adult. Educational handouts and transport from Bisbee is included.

Massi Point in the Chiricahua National Monument over looks the Sulpher Springs Valley.

Come visit the Southwestern Research Station Birding Paradise located at 5400 feet elevation in one of the world’s Biodiversity Hotspots.

The Southwestern Research Station is located in the heart of the Chiricahua Mountains and is famous for its close proximity to nesting Elegant Trogons, a large diversity of hummingbirds, and other spectacular bird migrants from Central and South America. Enjoy cabin accommodations, cafeteria dining, a reservoir for swimming, our hummingbird area and gift shop, and a multitude of hiking trails within walking distance or a short drive.

The Southwestern Research Station, located 5 miles from Portal, AZ, is hosting 7 day/6 night birding tours in Cave Creek Canyon, an area of high bird species diversity. Each trip is limited to 10 persons or 5 couples. Registration for tours is one month prior to tour date.

The Chiricahua Mountains of S. E. Arizona afford some of the best birding in the United States. Our 6 night Bird and Nature Tours include:

— Round trip transportation from the Tucson airport;

— Double-occupancy in our newly remodeled cabins, including a small kitchenette;

— Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner in the SWRS dining area;

— Hearty and sumptuous sack lunches and bottled water on day field trips;

— Professional guide and all park entrance fees;

As space permits, people other than scientists and researchers are welcome to stay at the SWRS. The Chiricahua Mountains are a prime destination for nature enthusiasts, with some 265 bird species recorded in the area, including nesting Elegant Trogons, Montezuma Quail, and over 13 species of hummingbirds. About 30 species are of sub-tropical origin and have their northern limits within this area.

Tour groups are welcome to stay at the Southwestern Research Station when space is available usually only during the spring and fall. Tour participants are housed in private rooms, double occupancy (some single occupancy rooms are available). All rooms have small kitchenette. Tour organizers must coordinate reservations and room assignments, and handle payment. Each room in our newly remodeled triplexes has either two single beds or one king size bed. Additionally, each room has a comfortable sitting area that includes a sofa that can convert to a bed, a private bathroom, and a kitchenette unit with microwave, coffee maker, and small refrigerator. The room cost includes three ample, delicious meals, served cafeteria style. Handicap accessible rooms are available.The cost per room, including three meals, is $90.00/person/night double occupancy or $130.00/night single occupancy.

Individuals may make reservations from 1 March to 15 June and from 1 September to 31 October. All rates include three full meals (vegetarian option) in our cafeteria where you have the opportunity to chat with other visitors and share birding experiences. On those days you wish to travel to more distant areas to bird watch, we will provide you with a sack lunch.

Cave Creek on the east side of the Chiricahua Mts where the Apache once farmed and where the Southwest Research Facility now calls home.

Biological Field Station located nestled in the Chiricahua Mountains in Southeastern Arizona, there the Southwestern Research Station (SWRS) is a year-round field station under the direction of the Science Department at the American Museum of Natural History (New York, NY). Since 1955, it has served biologists, geologists, and anthropologists interested in studying the diverse environments and biotas of the Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona. Southwestern Research Station, P.O. Box 16553, Portal, AZ 85632; FAX: 520-558-2018 http://research.amnh.org/swrs/about-swrs

Mt. Lemmon – At 9157 feet, Lemmon is the highest peak in the Santa Catalina Mountains. Vegetation ranges from saguaro-palo verde desert scrub at its base to mixed conifer forest at the summit. The drive from Tucson is via the winding paved Catalina Highway with frequent precipitous slopes that give majestic views of southern Arizona. Many miles of trails are available, traversing lush mountain meadows, dark forests and open woodlands of pine and oak. A remarkable variety of birds can be found April through September, including Red-faced, Olive, and Grace’s Warblers, Hepatic Tanager, Greater Pewee, Zone-tailed Hawk and many more.

Huachuca Mountains – Home to some of the best birding in Arizona. The superlative quantity and diversity of hummingbirds are probably unmatched in the U.S. and nowhere else north of Mexico are Buff-breasted Flycatchers more common. Spotted Owls and Elegant Trogons are also highlights. The main birding areas are in canyons on Fort Huacuhuca and the Coronado National Forest and at privately-owned feeders.

Santa Ritas (Madera Canyon) – Madera Canyon is one of the most famous birding areas in southeast Arizona. This canyon’s habitat consists of riparian woodland along an intermittent stream, bordered by oak woodland and mountain forests. The road enters through desert grassland and ends above the oak woodland, where hiking trails lead up the “sky island” through pine-oak woodland to montane conifer forest and the top of Mt. Wrightson (elevation 9453 feet). The spectrum of birds found in these varied habitats includes four tanagers: Summer, Hepatic, Western and Flame-colored as an occasional breeder. Hummingbirds, owls, flycatchers and warblers are also very well represented in this area.

Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve is the centerpiece of Santa Cruz County’s birding hot spots. This sanctuary, owned and managed by The Nature Conservancy, is one of the best birding spots in the Southwest. This lush riparian area provides habitat for over 200 species of birds plus rare fish, frogs, and plants. Gray Hawks nest in the large Fremont Cottonwoods along the creek, and Zone-tailed and Common Black-Hawks are occasionally seen. Over 20 species of flycatchers have been recorded on the preserve, including Thick-billed Kingbird and Northern Beardless-Tyrannulet. Recent rarities include the first known Sinaloa Wren in the United States. The preserve is on the west side of Patagonia; turn off Hwy 82 at Fourth Avenue, then follow the signs to the visitor center. The Nature Conservancy charges a general admission fee of $5.00 per person for adult non-members, $3.00 per person for adult members of TNC. Children under 16 and Patagonia residents are admitted free. Admission is valid for 7 days from the date of purchase; annual passes are available. The preserve is closed Mondays and Tuesdays year round, and visiting hours vary seasonally.

Southwest of Patagonia is the famous Roadside Rest Area. Many rare or hard-to-find birds have been sighted here, the most famous of which are the Rose-throated Becards that often nest in the Arizona Sycamores along Sonoita Creek across the highway from the rest area.

BOSQUE DEL APACHE WILDLIFE PRESERVE

Make plans to attend the 26th Annual Festival of The Cranes, Nov 19-24, 2013. Six great days of workshops, tours, lectures, hikes, special activities, and wildlife exhibitions. Register today and don’t miss out on this unique festival celebration!

The tour loop is a 12 mile, one-way graded road with a two-way cut-off which divides the full tour into a shorter South Loop of 7 miles and a North Loop of 7.5 miles. Both portions provide excellent winter viewing of wetland wildlife and raptors; the North Loop passes close to daytime winter foraging areas of cranes and geese. In spring and early fall; both loops provide close viewing of shorebirds and waterfowl. During the summer, impoundments adjacent to the North Loop are drained for vegetation management, but wild turkeys, songbirds and mammals may be present. Summer wetlands for waterfowl are along the South Loop, and along a seasonal road which is open April 1 to September 30. Stop as often as you wish along the tour loop to view wildlife; just pull to the side so others can pass. If you remain inside your vehicle, it serves as a blind so wildlife may remain closer while being viewed. Viewing platforms along the tour route accessible to people with disabilities offer viewing of cranes and geese during fall and winter. Some are equipped with a spotting scope.

Click here for videos of Bosque del Apache….

BE SAFE WHILE BIRDING IN THE SOUTHWEST… HERE’S HOW, CHECK IT OFF !

HUMMINGBIRD

$6.00 per person. Conservancy members and Cochise County residents, $3.00 per person. Children under 16 – FREE. There is no admission charge the first Saturday of every month. Annual passes available, as well as two-fer that covers this preserve and Patagonia-Sonoita Creek ($10 general public). Group visits require prior arrangements. Please call (520) 378-2785. 27 E. Ramsey Canyon Road, Hereford, AZ 85615

Open 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Closed Tuesdays/Wednesdays. Preserve parking is limited to 23 spaces. Spaces are available on a first-come, first-served basis.

Entrance to Madera Canyon, one of Southern Arizona’s favorite places to look for feathered winter visitors.

Madera Canyon, one of the most famous birding areas in the United States, is a north-facing valley in the Santa Rita Mountains with riparian woodland along an intermittent stream, bordered by mesquite, juniper-oak woodlands, and pine forests. Madera Canyon is home to over 250 species of birds, including 15 hummingbird species. Visitors from all over the world arrive in search of such avian specialties as the Elegant Trogon, Elf Owl, Sulphur-bellied Flycatcher, and Painted Redstart.

MADERA CANYON is 25 miles south of Tucson and 11 miles east of Green Valley. Turn east off of I-19 at the Continental Exit 63. Follow the signs to Whitehouse Canyon Road and on to the Forest boundary, about 11 miles. At the end of the road at the parking lot, the trailhead leads to Old Baldy.

In the Santa Rita Experimental Range below Madera Canyon can be found birds of the desert grasslands and brush, including Costa’s Hummingbird, Varied Bunting, Blue Grosbeak, Scaled Quail, Phainopepla, Botteri’s, Cassin’s, Black-throated, Brewer’s, and Rufous-winged Sparrows.

At Proctor Road, most birders walk the productive first section of the trail to Whitehouse Picnic Area to find Northern Beardless-Tyrannulet, Sulphur-bellied Flycatcher, Bell’s Vireo, Lucy’s Warbler, Blue Grosbeak, Varied Bunting, Summer Tanager, and sometimes Yellow-billed Cuckoo. The dirt road shortly above the parking lot may have Western Scrub-Jays and a Crissal Thrasher. Farther up the road, the Madera Picnic Area has Acorn and Arizona Woodpeckers, Mexican Jay, Bridled Titmouse, Painted Redstart, and Dark-eyed Junco. Three Myiarchus flycatchers , Western Wood-Pewee and Hepatic Tanager can be found here in season. Watch overhead for Zone-tailed Hawk among the Turkey Vultures.

INCA DOVE

The road to Madera Canyon enters through desert grasslands and ends in juniper-oak woodland, where hiking trails lead up in the “sky island” through pine-oak woodland to montane conifer forest and the top of Mt. Wrightson (elevation 9,453 feet). The spectrum of birds found in these varied habitats includes four species of tanagers: Summer at Proctor Road, Hepatic starting at Madera Picnic Area, Western up the trails in the conifers, and Flame-colored as an occasional breeder. Hummingbirds, owls and flycatchers are also very well represented in this area. Montezuma Quail are inconspicuous but present near grassy oak-dotted slopes. Madera Canyon makes a large dent in the northwest face of the Santa Rita Mountains. Its higher elevation grants relief to desert dwellers during the hot months and allows access to snow during the winter. A world-renowned location for bird watching, Madera Canyon is a major resting place for migrating species, while the extensive trail system of the Santa Rita Mountains is easily accessed from the Canyon’s campground and picnic areas. Madera Canyon has a long and colorful history. The Friends of Madera Canyon, a cooperating volunteer group, has developed a small booklet that can be requested at the gatehouse. Elegant Trogons are most often found along the first mile of either the Super Trail of the Carrie Nation trail. Hermit Thrush, American Robin, Plumbeous Vireo, Painted Redstart, and Dusky-capped Flycatcher are common along the trails. Yellow-eyed Juncos breed higher up towards Josephine Saddle.Night birding is a Madera canyon highlight, especially in May. Listen for Western and Whiskered Screech-Owls, Elf Owls and the much rarer Flammulated and Spotted Owls. Whip-poor-wills are in the forest and Common Poorwills can be heard near Proctor and below. Lesser Nighthawks, Barn and Great Horned Owls often fly across the road through the beam of your headlights as you approach the canyon.

A Coronado Recreation Pass or a National Interagency Recreational Pass must be displayed. Day Pass $5. Week Pass $10. Annual Pass $20

BABY HORNED OWLS

Muleshoe Ranch Service, Gailuro Mountains, Arizona

In southeast Arizona, the great Sonoran desert and the Chihuahuan desert reach out to meet one another. Lofty mountains with large undulating flat basins provide runoff to the streams and tributaries of the San Pedro River. The river is born in Mexico and flows north with life-sustaining water to produce a desert wetland, a sanctuary for year-round mountain and desert species, and a rest stop for flocks of migrating birds.

Breeding diversity in southern Arizona riparian areas is higher than in all other habitats combined, and Western riparian areas contain the highest non-colonial bird breeding densities in North America. More than 400 species of birds have been recorded within the San Pedro River basin’s major habitats. Nearly one-half of the United States’ bird species frequent the area as they migrate. The tremendous importance of the San Pedro River system was established in 1988 when it was recognized as this country’s first Riparian National Conservation area. The river is a 140-mile long desert oasis — a dry San Pedro would mean no green corridor or birds migrating across the arid land of the Southwest. The consequences are hard to fathom. Careful conservation planning is necessary to help preserve the right kind of natural areas in just the right places in order to keep migratory corridors connected. Purchased by the Nature Conservancy in 1982, Muleshoe Ranch is one of the most biologically diverse desert riparian areas in the world.

It’s easy to see why people fall in love with desert habitats after a late-afternoon walk in Sabino Canyon. When the setting sun casts a golden glow on the mountains, I have to remind myself that I visit this place with the intention of birding. I’m brought back to the task at hand by the inquisitive wurp of the locally common Phainopepla and the activity of bold, noisy Cactus Wrens. On spring evenings, Elf Owls can be heard barking from the surrounding saguaros, and they are often joined by Common Poorwill, Western Screech-Owl, and Great Horned Owl. Winter is my favorite time to bird the canyon. I like to walk the lower stretch of the creek to where an old dam has backed up moisture and created a thick willow forest. In the colder months, it’s possible to see four species of towhee here: Green-tailed, Canyon, Abert’s, and Spotted. Numerous rarities have also shown up over the years. Sabino Canyon’s variety of habitats (including a rare desert creek lined with riparian vegetation) has prompted its inclusion as an Important Bird Area in National Audubon’s program in Arizona. The birds seem to know of the canyon’s regional importance. They are abundant, taking advantage of the excellent protected habitat in the area. – Matthew Brooks

Residents: Abert’s Towhee, Black-chinned Sparrow, Western Screech-Owl, Northern Cardinal, Pyrrhuloxia, Greater Roadrunner, and Rufous-crowned, Rufous-winged, and Black-throated Sparrows. Summer: Northern Beardless-Tyrannulet, Elf Owl, Brown-crested Flycatcher, Bell’s Vireo, Broad-billed Hummingbird, Lucy’s Warbler, Bronzed Cowbird, Hooded Oriole, and Varied Bunting (uncommon). Winter: Hermit Thrush, Lawrence’s Goldfinch, and Green-tailed Towhee. Rarities: Plain-capped Starthroat, Violet-crowned Hummingbird, Winter Wren, and eastern warblers.

Sabino Canyon tours offers a narrated, educational 45-minute, 3.8 mile tour into the foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains. The trams have nine stops along the tour with several restroom facilities and picnic grounds located near Sabino Creek. The tram turns around at Stop #9 and heads back down to the Visitor’s Center, at which point riders may remain on board and hike back down. Trams arrive on average every 30 minutes.

Summer Hours: (July through mid-December) Monday-Friday: 9:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Weekends & Holidays 9:00 a.m. – 4:30 p.m.

Winter Hours: (mid-December – June) Monday-Sunday 9:00 a.m.-4:30 p.m Visitor Center: Monday-Sunday 8:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m.

Fees: $8.00 adults, $4.00 children 3-12. Children 2 and under are free.

Driving from Tanque Verde Road in Tucson turn north on Sabino Canyon Road 4 miles to the Sabino Canyon Recreation Visitor Center or the coordinates: 32°18’36.09N 110°49’20.27W 5700 N. Sabino Canyon Rd. Tucson, Arizona 85750 (520) 749-8700

911 OR ARIZONA / SOUTHWEST BIRDING HOT SPOTS AND RARE SIGHTINGS

Suffering from drought the once three pond compound has shrunk up and now has only the main pool.

Organ Pipe Cactus scheduled tours to historic Quitobaquito last year and we hope they planned a couple weekend tours to give visitors an opportunity to take part in the tour. Last year’s tours were scheduled: February 8, 15, 17, 22 & 24 ; March 1, 8 & 15.

Anyone wishing to reserve a seat on the van this year should call 520-387-6849, extension 7302 for and see if they are taking reservations. The number of available seats were limited, so reservations were required. No personal vehicles are permitted on the tour. A National Park Service van will transport visitors to Quitobaquito with a Park Ranger who will provide a guided tour of the area. Participants should arrive at the Kris Eggle Visitor Center no later than 7:45 a.m. The tour will leave the visitor center after a safety briefing. The van will return at approximately noon. Children must at least 12 years old and accompanied by an adult.The walking tour will last approximately two hours and be through the historic area over uneven ground. Participants should bring a snacks, water, sunscreen, brimmed hat and wear sturdy shoes. People may bring binoculars and cameras, however the van does not have storage capacity so large camera bags and tripods will not fit. All participants will be required to go on the walking tour and stay as a group with the Park Ranger.

BIRDING IN ARAVAIPA CANYON … CLICK HERE

Aravaipa is famed as a birder’s paradise, with nearly every type of desert songbird and more than 150 species documented in the wilderness. Isolated Aravaipa Canyon is one of the true natural Arizona wonders, featuring a desert steam, majestic cliffs and bighorn sheep. Located about 50 miles northeast of Tucson, the preserve includes lands at both the east and west end of Aravaipa Canyon, as well as preserved lands intermixed with public land on the canyon’s south rim. The 9,000 acres owned by The Nature Conservancy are managed in conjunction with about 40,000 acres of federal lands. Preserve elevation ranges from 2,800 feet at the west end of the canyon bottom to 6,150 feet on Table Mountain. The 10-mile long central gorge, which cuts through the northern end of the Galiuro Mountains, is a federal Wilderness Area managed by BLM. Access into Aravaipa Canyon is by permit only and available only through BLM.Among the more than 200 species of birds found at Aravaipa are black and zone-tailed hawks, peregrine falcon, yellow-billed cuckoo, Bell’s vireo, and beardless tyrannulet. Saguaro and other cacti grow on Aravaipa’s rocky ledges, providing nest sites for small owls, woodpeckers, and other desert birds. Mesquite-covered grassy flats furnish cover for abundant birdlife on the canyon floor. Birds of prey include peregrine falcon, common black-hawk, zone-tailed hawk, and elf owl. Migratory songbirds include vermilion flycatcher, black phoebe, canyon and rock wrens, white-throated swift, yellow warbler, and Bell’s vireo. The sheer cliffs are good places to look for bighorn sheep. Riparian species include javelina, Coue’s white-tailed and mule deer, coyote, mountain lion, ringtail, and coatimundi. Nearly a dozen bat species flourish in Aravaipa’s small caves, emerging at dusk to hunt for insects. Aravaipa Creek is often considered the best native fish habitat in Arizona.A Wilderness permit is required from BLM. While a hiker can cross from the west end of Aravaipa Canyon Wilderness to the east end by hiking only 11 miles, the entrances are nearly 200 miles apart by road. Canyons can flood; be aware of weather forecast before entering.

Picacho Reservoir is a rarity in central Arizona: a marshy oasis in the midst of an arid cotton-growing region. The lake draws waterfowl and shorebirds, and attracts unusual vagrants. The reservoir is less than 60 miles from both the Phoenix and Tucson areas. Despite its proximity, the reservoir has been a somewhat obscure destination for Phoenix birders; this article is intended to serve as a guide for MAS members and others who may wish to visit the area. The reservoir was built in the 1920’s as part of the San Carlos Irrigation Project. The reservoir’s original purpose was water storage and flow regulation for the Florence-Casa Grande and Casa Grande Canals. The lake’s design capacity was 24,500 acre-feet of water, with a surface area of over 2 square miles. Over the years, siltation and vegetation have reduced the capacity and surface area, so that much of the reservoir is a shallow marsh with extensive stands of cattails and rushes. Water level is highly variable, and the lake is completely dry in some years.

Turn east onto the Selma Highway (which becomes a dirt road). Continue on the Selma Highway 1 mile east to a T intersection in front of some electrical equipment and an embankment. Turn right (south) and go 0.3 mile to a canal road; turn left and follow the canal about 0.6 mile. The reservoir levee will be in front of you; take the road up the levee. This is the “southwest corner” of the reservoir, with a view over the main body of the lake. The tour continues counterclockwise around the reservoir from here. If the water is low, you can drive down into the lakebed from the levee at the southwest corner; park here and walk toward the water for closer views Returning to the SE corner, take the road NNE along the canal. This road has a stand of mesquite along the left (west) side, with a similar stand across the canal to the east. Species such as Bell’s Vireo and Lucy’s Warbler may be seen here in spring and summer, and Pyrrhuloxia and Cardinal are both found along the road. Phainopepla also frequent the mesquites. The road is wide enough to park along the shoulder and walk. Occasional passages break through the mesquite to the west, into an open area. Thrashers and Abert’s Towhee may be found along the edge of the open space, and Gambel’s Quail are common. Ladder-backed and Gila Woodpeckers may be found in the mesquites. From fall through early spring, wintering sparrows may be found, including Lark Sparrow and Vesper Sparrow. The road continues generally north along the canal for about 2.9 miles before crossing a large floodgate. This gate is the main feeder for the reservoir; water may be sent down a channel heading WSW toward the lake. Just before the floodgate, a road heads SW (marked “E”) into the open region which may be birded for arid-scrub species. Just past the floodgate, the road around the reservoir turns WSW, while the canal road continues north. This is the “northeast corner”. Turn left (WSW) to continue on the reservoir road.

Las Cienegas National Conservation riparian district is a protected area for birding without hunting.

At Cienega Creek Preserve, a perennial creek channel is surrounded by mountains and rocky hills.

Las Cienegas NCA – In 2000, the 45,000-acre Empire Cienega Resource Conservation Area was expanded and renamed Las Cienegas National Conservation Area. Starting in 2010, the BLM began working to restore the high desert grasslands to their original condition by removing much of the mesquite that invaded the arroyos during the cattle boom years. Several areas are now being used for the reintroduction of endangered black-tailed prairie dogs. Varied habitats including a perennial stream with cottonwood-willow riparian areas, cienegas (small marshlands), juniper-oak woodlands, sacaton grasslands and mesquite bosques support diverse bird species.

A section of the creek within the Preserve has been designated as a “Unique Water of Arizona”. The mature cottonwood and willow trees that line the creek are a dramatic contrast to the surrounding Sonoran Desert. Rich cultural and historical features are displayed here as well. One of the most significant vantage points is the area near the Marsh Station Road Bridge over Cienega Creek. The visual features and relatively good access from this point make it one of the most popular places to visit on the Preserve. The preserve is a protected riparian system without designated trails or facilities for visitors. The Arizona Trail system along the edge of the preserve allows equestrian, biking, and hiking use. The management plan for Cienega Creek Preserve restricts the number of visitors per day, and permits are required for access. Take a casual stroll through the cottonwoods and willows to spot songbirds as well as raptors. Start at the Gabe Zimmerman Davidson Canyon Trail head at Cienega Creek Natural Preserve, 16000 E. Marsh Station Rd.

More info 615-7855 or eeducation@pima.gov.